Dubai Expo

Canada’s Storytellers – Trésor Nzengu Mpauni at the Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

Trésor Nzengu Mpauni

Trésor’s Story

On a large stage, Congolese singer and rapper Ced Koncept plays to an enormous crowd of dancing fans. He is followed by a Malawian gospel singer, who then passes the stage to a reggae band. Up-and-coming youth performers from around the world occupy a neighbouring stage. Push your way through throngs of cheerful festival-goers and you will find other vibrant cultural presentations, from theatre productions and poetry recitals to fashion shows and craft booths. This joyful celebration of music, arts and culture is the Tumaini Festival, and it is all taking place in a refugee camp.

The Tumaini Festival is the brainchild of Trésor Nzengu Mpauni, also known by the stage name Menes la Plume, a popular Congolese hip-hop artist, writer and slam poet. Forced to flee his home country, Trésor came to Malawi as a refugee, relocating to the Dzaleka Refugee Camp. As Trésor quickly discovered, refugees face many barriers to integration in Malawi. The country’s encampment policy restricts refugees’ rights to move freely, gain employment or access education outside of the camp, leaving the population cut off from opportunities to improve their lives and contribute to their host society. Understanding that Malawians would benefit greatly from the talent and diversity he saw all around him in the camp, Trésor founded Tumaini Letu (Swahili for “Our Hope”), a non-profit organization dedicated to promoting the social, economic and cultural inclusion of refugees through arts and culture. Two years later, in 2014, Trésor organized the first Tumaini Festival as a platform for intercultural harmony, mutual understanding and peaceful co-existence between Malawi’s refugee and host communities.

Over the course of six three-day festivals, Trésor has united over 300 performers from 18 countries and attracted more than 99,000 attendees from around the world. The Tumaini Festival is not only the world’s lone music festival hosted in a refugee camp, but it has also become one of Malawi’s premier events. As the main source of revenue for Dzaleka, the festival offers employment and business opportunities for refugees before, during and after the event. In addition to performing, many refugees sell food and crafts to festival-goers or welcome them into their homes through the festival’s home-stay program.

Through his work with Tumaini Letu, Trésor has inspired a tremendous shift in societal views of refugees in Malawi and throughout the world. He has shown that a refugee camp can be a vibrant place where people gather to celebrate diversity. He has shown that when societies open their doors to refugees, they are inviting in incredible resilience, talent and opportunity.

Located about 40 km outside Lilongwe, Malawi’s capital city, the Dzaleka Refugee Camp was established by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in 1994 in response to a surge of forcibly displaced people fleeing genocide and conflict in Rwanda, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Prior to becoming a refugee camp, the Dzaleka facility was a political prison housing some 6,000 inmates. Today, Dzaleka is the only permanent refugee camp in Malawi. The camp hosts over 50,000 refugees and asylum seekers from approximately 15 nationalities, with hundreds more arriving each month. Malawi’s encampment policy bans refugees from residing outside the camp, restricting their access to tertiary education and formal employment.

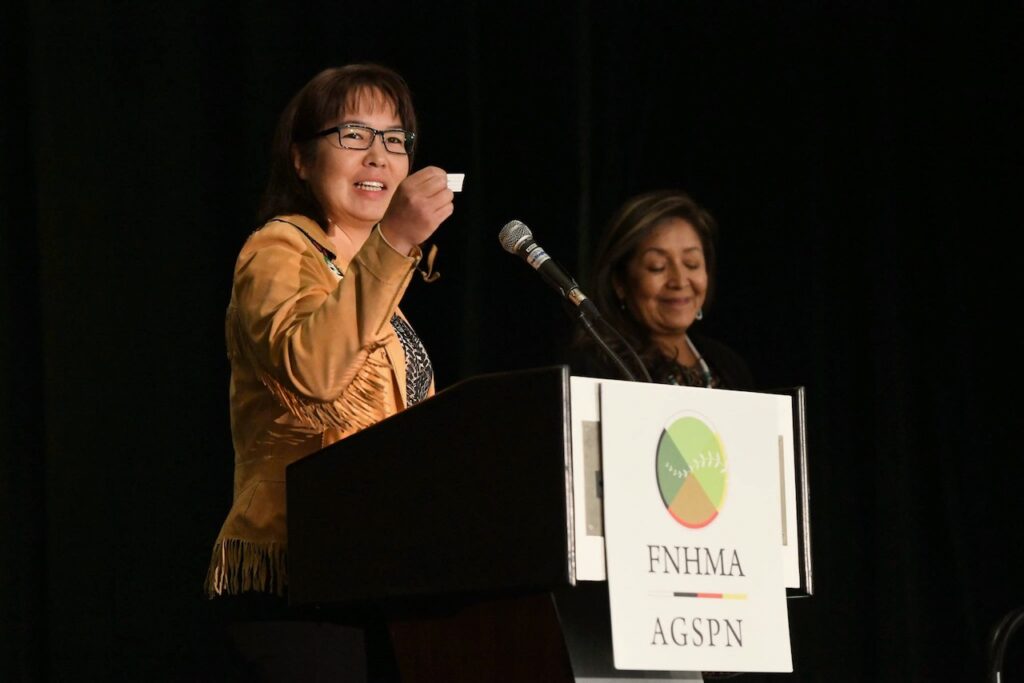

Rose LeMay

Rose’s Story

Rose LeMay is from the Taku River Tlingit First Nation in northern British Columbia, Canada. A survivor of the Sixties Scoop, the mass removal of Indigenous children from their homes and families that took place in Canada throughout the 1960s, Rose was taken from her community as a baby and raised by a non-Indigenous family. She had to figure out who she was, far away from anyone who looked like her. She experienced racism regularly. Rose came to recognize that her experience gave her a unique opportunity. She had a foot in two worlds, and she resolved to use her position to increase understanding between those worlds and to build a more pluralistic Canada so that her children would not have to experience the discrimination that she did.

Rose spent 20 years working for the Government of Canada, advocating for a more inclusive health system for Indigenous communities, with a focus on mental health. She led the development of a mental health plan for survivors and attendees of the Residential School system who were testifying at the first national Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) event, and in 2016, she led the World Indigenous Suicide Prevention Conference abut culture as a protective factor, the first to be hosted in Canada.

In 2017, Rose founded the Indigenous Reconciliation Group (IRG) to provide adult education and organizational training on Indigenous cultural competence and reconciliation. The IRG raises awareness about the types of racism that exist for Indigenous people in Canada and how Canadians can work together for Indigenous inclusion—whether by ensuring that indigenous clients receive the same quality of care from frontline services providers or by supporting organizations to educate their employees about racism.

Through the IRG, Rose raises awareness via media outreach and speaking engagements. She helps organizations shift their policies and programs to support reconciliation by implementing the TRC’s Calls to Action. Rose’s courses have reached more than 5,000 people across Canada. The Government of Nunavut and British Columbia’s Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation have sought out her trainings, with the latter engaging with IRG specifically to consult on a strategic plan to enact the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

As Rose points out, reconciliation is a journey that Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada choose to take together, with leaders and allies and change-makers across all sectors of Canadian society pushing to do better for each other and for the country.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established in 2008 with the purpose of documenting the history and lasting impacts of the Residential School system, through which 150,000 indigenous children were taken from their communities and sent to state-funded institutions where they were stripped of their culture and severely mistreated. The TRC determined that the Residential School systems amounted to a cultural genocide of Indigenous people. In addition to guiding Canadians through the difficult discovery of the facts behind the Residential School system, the TRC was meant to lay the foundation for lasting reconciliation across Canada. In 2015, the Commission came up with 94 Calls to Action that were presented to the Government of Canada regarding reconciliation between Canadians and Indigenous peoples. In 2021, the unmarked graves of thousands of Indigenous children were uncovered across former Residential School sites. These tragic reminders of the legacy of the Residential School system highlight the gravity of the violence, the importance of this conversation and the urgency of concrete actions toward reconciliation.

Lenin Raghuvanshi

Lenin’s Story

Growing up in Uttar Pradesh, Lenin Raghuvanshi was troubled by the gender inequality he witnessed in Indian society. As he got older, his awareness of discrimination only grew. While working with bonded labourers in India, Lenin recognized that none of the children bonded in the sari or carpet industries came from an upper caste. He identified caste, a deeply hierarchical and oppressive system of social stratification, as the root of multiple social conflicts and a major barrier to his dream of justice for all.

In 1996, with his wife Shruti Nagvanshi, Lenin co-founded the People’s Vigilance Committee on Human Rights (PVCHR), an inclusive social movement that challenges patriarchy and the caste system and advocates for marginalized groups in India. Through a grassroots, neo-Dalit approach, the organization works to unite Indians from all backgrounds, including Dalits (“Untouchables”) and Adivasis (Indigenous and Scheduled Tribes) to dismantle the caste system and champion diversity. Today, PVCHR has 72,000 members working against caste discrimination across five states.

Lenin has been credited with changing the discourse on Dalit politics in India. His efforts have brought the challenges facing India’s marginalized communities to both national and international attention. Lenin’s work extends beyond caste-based discrimination to advocating for the rights of children, women, migrant workers, torture survivors, religious minorities and any other community facing systemic discrimination in India. His initiatives range from folk schools that educate youth about human rights to Jan Mitra Gaon (“people-friendly villages”), a model he implements in conservative slums and villages to strengthen local institutions and to promote non-violence alongside basic human rights. In a country as vast and diverse as India, Lenin’s work to promote inclusion and basic rights for all is complex but essential. Across his varied efforts, Lenin is driven by the knowledge that every life has intrinsic value, and no case is too small. Through championing the inclusion of disenfranchised people across India, Lenin is fighting for the country he loves. He is doing all he can to ensure that rather than be torn apart by its remarkable diversity, India will be strengthened by it.

One of the world’s oldest civilizations, India is on its way to becoming the world’s most populous nation. India is incredibly diverse across multiple areas, including religion, language, caste and tribe. Close to 80 percent of India’s 1.4 billion people are Hindus, but there are also millions of Muslims, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains. India’s caste system is a social hierarchy dating back some 2,000 years. It categorizes Hindus at birth, dictating their place in society. At the bottom of this constructed hierarchy are Dalits and Adivasis, who together make up nearly a quarter of India’s population. These groups are societal outcasts, facing social and economic marginalization and discrimination. Although India’s constitutional framework recognizes group-differentiated rights, the country has experienced a growing climate of intolerance in recent years, fueled by the rise of right-wing nationalism. There is real concern that India’s inclusive citizenship policies and welfare architecture—championed and built over the past 70 years—are being dismantled, threatening the country’s pluralistic fabric.

Community Building Mitrovica

The Team’s Story

In northern Kosovo, the Ibar River splits the city of Mitrovica in two. Ethnic Albanians live in the city’s south, and ethnic Serbs live in the north. Although a bridge connects the two sides, it has become emblematic of conflict, rather than a means to connect. The bridge is patrolled by heavily armed international forces, and vehicular traffic is blocked by piles of concrete rubble. Few pedestrians dare to cross it, and some young people in Mitrovica have never encountered anyone from the other side of the Ibar. Against a backdrop of fear, mistrust and division, Community Building Mitrovica (CBM) works to rebuild community links, facilitate inter-ethnic dialogue and promote social integration.

CBM was established as the first grassroots civil society organization in Mitrovica following the 1998–99 Kosovo War. After opening their doors in 2001, CBM facilitated the first contact between the city’s two groups and have been a leader in the region’s inter-ethnic co-operation ever since. Most of CBM’s work is focussed on providing safe spaces for residents of Mitrovica, both ethnic Serbs and Albanians, to connect and establish relationships based on a shared interest or need.

The organization’s activities have often led to sustainable initiatives that continue for years after a project ends: for example, the multi-ethnic Women in Business network which supports female entrepreneurs; the Mitrovica Women Association for Human Rights which actively promotes women’s participation in peacebuilding; and the Mitrovica Rock School, which, in a nod to the city’s history as a rock music hub, brings Serb, Albanian, Macedonian and Roma youth together to play music. CBM is currently working with the University of Pristina, a public education institution in Kosovo, to establish a master’s program in Peacebuilding and Transitional Justice.

CBM has gone beyond its mandate to connect diverse communities, going above and beyond to empower community members as active participants in decision-making processes for community projects and interventions. The organization has become a reliable information source for international and local organizations working on peacebuilding, human rights, economic development and social cohesion. Through years of building trust with communities on both sides of the Ibar, CBM has changed the mindsets of thousands of citizens and contributed in tangible ways to advancing pluralism in Mitrovica and throughout Kosovo.

Following the 1998–99 war in Kosovo, Serbs moved from the south of Kosovo to the north, while Albanians moved from the north to the south. This division was echoed in Mitrovica, which remained a hot spot for ethnic tension in Kosovo. There was limited interaction between the communities, except when they collided in violent and sometimes deadly conflict. Today, tensions between the two groups remain high. Rioting in October 2021 reignited fears of escalated violence in Mitrovica.

Carolina Contreras

Carolina’s Story

Born in the Dominican Republic (DR), Carolina Contreras immigrated to the US as a young child. As an adolescent, she faced the strictly enforced hair culture that leads many Afro-Latinas to straighten their hair to avoid ostracism at work and school. As in many places around the world, white European beauty ideals, such as sleek, straight hair, are celebrated in the DR and by the Dominican diaspora in the US, while afro-textured hair is seen as unkempt, unclean and undesirable.

Following her post-secondary studies, Carolina embarked on a journey of self-discovery which took her back to the DR. It was around this time that she started to question the deeply embedded colonial narratives that are prevalent in Dominican society. After years of relaxing and straightening her hair, she decided to embrace her natural hair as a celebration of her identity as a woman of colour.

Carolina started a natural hair care blog for women and girls who might want to do the same. Her blog quickly expanded into a global movement, reaching thousands of people in countries all over the world. In 2014, Carolina opened Miss Rizos Salon, the first all-natural hair salon in the DR specializing in curls. The salon, which grew from a team of two to a team of 20, has sparked a trend of curly hair care and celebration, inspiring dozens of natural hair salons across the country. In 2020, Carolina opened a second salon in New York City’s Washington Heights neighbourhood, home to one of the largest Dominican communities in the US.

Today, Carolina’s work has moved beyond the walls of her salons. Through online advocacy, summer camps, school workshops and a comic book starring a Black, curly-haired female superhero, Carolina’s organization has empowered thousands of girls to celebrate diversity, challenge stereotypes and reconsider long-held ideas about what it means to be beautiful and worthy of inclusion. The organization has also trained Peace Corps volunteers to teach a Miss Rizos-based curriculum of self-empowerment, identity and constitutional rights in workshops across the DR to empower women and girls to challenge anti-Black discrimination by standing up against those who perpetuate harmful prejudice against curly hair.

Discrimination against curly hair is prevalent across the Americas, including in countries with large Black populations. The Dominican Republic, which has one of the largest Black populations outside of Africa, has a long history of anti-Black racism as a legacy of hundreds of years of colonialism. White Eurocentric beauty standards are celebrated in media and popular culture, with many black Dominicans traditionally being pushed to deny their own identity in order to gain access to higher spheres of public life. Despite their long historical presence and their fundamental role in shaping the identity of the region, Afro-Latin Americans continue to face widespread discrimination.

ArtLords

ArtLords’ Story

A grassroots social movement that combines art and activism, ArtLords was founded in Kabul in 2014, when ArtLords’ “artivists”—artists and civil society activists—began painting murals on the city’s bomb-blast walls. Since then, ArtLords has been using street art, theatre and community outreach to campaign for peace, social transformation and accountability across Afghanistan and around the world.

When the Taliban advanced across Afghanistan in August 2021, ArtLords kept working. On the morning of August 15th, with the Taliban at the gates of Kabul, ArtLords’ artivists picked up their brushes outside the governor’s office, painting, as always, in celebration of diversity and unity. When they saw panicked people rushing from the building, they struggled, through chaotic streets, to return to the ArtLords gallery, where they learned that Kabul had fallen.

The Taliban has painted over many of the murals, replacing them with religious poetry or pro-Taliban messages, but ArtLords’ influence is not so easily erased. With over 2,000 murals across 20 Afghan provinces, the movement has spread messages of peace, justice and inclusion throughout the country, promoting and facilitating dialogue between Afghans. While painting a mural, ArtLords’ artivists urge passersby to pick up a paintbrush and join in. They encourage Afghans from all religions, tribes and ideologies to develop the murals collaboratively and to discuss them openly. ArtLords has turned blank walls into vibrant spaces for collaboration, reflection and conversation, giving Afghanistan’s diverse communities opportunities to connect and build trust.

ArtLords has also launched an art gallery, an arts-and-culture magazine, a café and a wide range of outreach programs, including theatre and painting workshops. In partnership with Afghanistan’s Ministry of Education, ArtLords worked with 38 high schools, co-developing murals with students to spark discussion and reflection on key social issues. ArtLords’ Let’s Talk Afghanistan campaign empowers youth from diverse communities to come together to envision and work towards a democratic, inclusive future for their country.

Today, the work of ArtLords is continuing from exile. With galvanized commitment to freedom of expression and renewed belief in the transformative power of art, they are coordinating new murals in Albania, Italy and the United States (US), and have begun a campaign to start art therapy sessions for Afghan refugees in camps across various countries.

Afghanistan is a diverse country made up of numerous ethnolinguistic groups with an incredibly rich cultural history. The country was under the control of the Taliban from 1996 until the United States-led invasion in 2001. The Taliban regained control of the country in August 2021. In the intervening 20 years, Afghanistan experienced significant advancements in civil society, media, education and knowledge, along with a vibrant re-emergence of arts and culture. Violence over the past decade has impacted the lives of all Afghans, regardless of ethnicity, language or location. The effective and equitable management of Afghanistan’s rich diversity will be critical to the country’s future stability—and central to sustaining peace and prosperity in the country and the region at large.

All Out

All Out’s Story

All Out is a connector. When a crisis or opportunity arises, All Out’s international team works with grassroots, frontline LGBT+ groups to come up with inspiring ways to improve the lived experience of LGBT+ people in their societies. They bring local stories to a global audience to unite hundreds of thousands of people from around the world and offer them concrete ways to make a difference—to turn solidarity into action. All Out crafts powerful campaigns to mobilize global support for LGBT+ activists through digital storytelling campaigns that amplify their voices, online petitions that target key decision-makers and crowdfunding campaigns that raise hundreds of thousands of dollars to support local partner initiatives.

All Out’s results are powerful and wide-reaching. Their crowdfunding campaigns paid for food and sanitary supplies for LGBT+ refugees at Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya and the launch of Venezuela’s first centre for LGBT+ people. All Out’s pressure campaigns led to the removal of homophobic stereotypes from school textbooks in China, the altering of derogatory Google-generated translations for the terms “gay” and “homosexual” and the banning of conversion therapy in Germany. In Brazil, which has one of the highest rates of anti-LGBT+ violence in the world, All Out created Acolhe LGBT+ (“Welcome LGBT+”), a platform that connects volunteer psychologists—trained by All Out in caring specifically for LGBT+ people— with survivors of hate crimes and other at-risk members of the LGBT+ community. Through targeted mental health support focussed on dignity and autonomy, the program has given over 1,400 LGBT+ Brazilians, including members of the country’s underserved rural populations, the resources, support and freedom to fully live their identities—and to contribute in crucial ways to their broader communities.

Throughout the world, All Out is changing the conversation around LGBT+ rights. By harnessing the power of a vibrant global community, the organization is replacing narratives of fear and hate with those of the positive economic, social and cultural benefits of full equality for LGBT+ people. Through all its diverse and innovative efforts, All Out is fighting for a world in which no one has to sacrifice their family, freedom, safety or dignity because of who they are or who they love.

In more than 70 countries, it is a crime to be gay, and in 10 countries, it can cost you your life. Even in places where there are no anti-gay laws, LGBT+ people continue to experience violence, persecution and inequality. In every country across the world, LGBT+ individuals face discrimination based on sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. Recent years have seen a rollback of LGBT+ rights in the context of rising right-wing populism. Brazil is experiencing a surge in anti-LGBT+ violence, and in the United States, fatal violence against transgender people is on the rise. Across Poland, towns and provinces have declared themselves “LGBT Free Zones,” and new anti-LGBT+ legislation has been proposed in several countries including Hungary, Ghana, Uganda and Russia.

Namati Kenya

“Being recognized as a winner of the Global Pluralism Award for this work is a true honor. It is a testament to the idea that everyone – even those who have long been at the margins – can be an agent of change in creating a pluralistic society.”

Mustafa Mahmoud, Namati Kenya

Namati Kenya’s story

Botul, a mother of four and a member of Kenya’s Nubian community, was told that her children could no longer attend school because they did not have birth certificates. She could not apply for their birth certificates, however, until she received an identity (ID) card. In Kenya, a national ID card is required to vote, to move freely around the country and to access basic services, such as health care, education and employment. Unfortunately, obtaining an ID card is not easy for someone like Botul. As a member of one of Kenya’s predominately Muslim communities, she is one of five-million Kenyans who face a discriminatory vetting process when trying to acquire basic legal identity documents. While most Kenyans can acquire an ID card in a few weeks, many others from minority ethnic groups that are predominantly Muslim wait months or years—or never receive documents at all.

Botul eventually found the guidance she needed through Zena, a community paralegal trained by Namati Kenya. Zena helped Botul understand her rights and supported her through every step of the ID application process. Botul was able to obtain her ID and immediately applied for her children’s birth certificates. Now, while her children attend school, Botul is busy sharing her new knowledge with her community.

Through its Citizenship Justice program, Namati Kenya trains and deploys community paralegals to support and empower marginalized citizens to understand, use and—eventually—shape the law. Since 2013, Namati Kenya’s paralegals have assisted over 12,000 Kenyans apply for legal identity documents. With data collected from these cases, the organization tracks patterns of discrimination across the country and pushes for systemic change. Namati Kenya also spreads legal awareness through grassroots mobilization, door-to-door outreach, community forums and a rights-based community radio show. Currently, Namati Kenya is leading advocacy efforts on amendments to Huduma Namba, a new national biometric ID system, to ensure no Kenyans are excluded.

Working with and through a coalition of partners, Namati Kenya brings diverse communities together to recognize their common challenges and to engage in a national dialogue about “who is Kenyan” and what it means to belong. Creating these connections across diverse communities is a fundamental step in the establishment of an inclusive, pluralistic society. Through their work on citizenship justice, Namati Kenya is transforming the law from an abstract system that serves a few to a powerful, practical tool that all of Kenya’s diverse citizens can use to improve their lives and build a society that honors the rights and dignity of all its members.

Kenya, home to nearly 50 million people, has an incredibly diverse population that includes over 40 ethnic groups representing four major language groups. The country is also religiously diverse, with a Christian majority, a sizeable Muslim minority and communities adhering to Hinduism, Sikhism and Indigenous religions. Following a contested election in 2008, violence erupted along ethnic lines. After months of conflict, a new constitution was drafted to recognize the pluralistic nature of Kenyan society. Despite this, many minority groups, particularly Muslim-majority communities, are considered outsiders and struggle to be recognized as full citizens.