OnBoard Canada

A program of Ryerson University’s Chang School of Continuing Education

“Canada is a great example of a pluralistic country and yet, we still struggle to get it right. onBoard has helped change the way leadership looks in this country with an approach that should serve as a model to other countries struggling with representation and access to equal opportunities.”

Joe Clark, former Prime Minister of Canada and Chair of the Global Pluralism Award Jury.

OnBoard’s Story

Look around the table at the board members of Canada’s private and public sectors, and you will see a persistent disconnect with the make-up of the Canadian population. Canada has long been proud of its diversity, but the composition of its boards does not relay the same story.

onBoard Canada was created to address this gap between Canada’s decision-makers and its demographic reality. onBoard recognized that it was not enough to be a diverse country; Canada also needed to be actively inclusive. Without real inclusion, how could Canada’s leadership ever benefit from the country’s diversity?

To create pathways to leadership, onBoard Canada offers governance training to interested participants, and board matching to members of underrepresented communities. The organization also offers training to the not-for-profit and public sectors to help leaders recognize their own privilege and provide them with the tools to create more inclusive workplaces. As a program of Ryerson University’s G. Raymond Chang School of Continuing Education, onBoard Canada conducts research in partnership with the Diversity Institute about the lack of diversity in Canada’s leadership.

By helping underrepresented individuals claim a seat at the decision-making table, the organization ensures more Canadians have a say in the decisions that affect them. But Canada’s underrepresented groups are not the only beneficiaries. Boards are invigorated and strengthened by a wide range of voices and perspectives.

onBoard Canada has changed the make-up of not-for-profit and public boards in the Greater Toronto Area and in several cities across the country. It has trained and matched thousands of individuals to board opportunities, with over 1,000 appointments to more than 800 not-for-profit organizations, public agencies, boards and commissions.

By bridging the diversity and inclusion gap in Canada’s leadership, onBoard is raising the standards for modern governance. In the end, all of Canada benefits.

Canada is a diverse country, and recent demographic projections suggest that ethno-cultural diversity will continue to increase. By 2031, 29-32% of the country’s population will be made up of visible minorities. Other diverse communities within Canada have also gained greater visibility and are demanding recognition and representation. Individuals from LGBTQ+ communities are feeling safer to come out publicly; youth are seeking a voice at decision-making tables; and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission identified 94 highly publicized calls to action regarding reconciliation between indigenous peoples and Canadians. Yet leadership does not reflect this reality. In 2017, Ryerson University’s Diversity Institute found that visible minorities make up 3.3% of corporate board positions, an increase of less than 1% since 2014. Although women make up 48% of the workforce, in 2017 they only held 14.5% of all Canadian board seats in companies that disclose this information.

Adyan Foundation

“Adyan’s projects have successfully engaged thousands of citizens, bringing together youth, families and volunteers, to break down cultural and religious barriers and open up a conversation around shared citizenship and belonging. Despite religious tension in the region, Adyan is forging an inspiring vision for inclusive communities and spiritual solidarity across Lebanon and the Middle East”

Joe Clark, former Prime Minister of Canada and Chair of the Global Pluralism Award Jury.

Adyan’s Story

In a short video on Taadudiya, an online platform created by the Adyan Foundation, Jihad and Rita start a music school in a rural Lebanese community and children come from near and far to attend. In another video, Sameh and Hanaa tackle religious sectarianism in Egypt by bringing Christian and Muslim children together to play soccer. In another, Salam and Zeinab overcome their religious differences and develop a deep friendship based on a shared passion for their work in radio and television.

Founded in 2006 by a group of Christians and Muslims, Adyan Foundation works in Lebanon and across the Middle East to foster cultural and religious diversity through grassroots initiatives in education, media and public policy, and intercultural and interreligious relations. Their goal is to help people develop their faith with an openness towards others and a commitment to serving the common good.

One of Adyan’s most recent initiatives, Taadudiya, or “pluralism” in Arabic, is challenging extremist narratives of hate and violence with non-biased information on religious beliefs and traditions with videos of everyday people engaged in religious inclusion in their communities. In its first year, the online platform has reached 38 million people.

Adyan operates on many levels. Their interfaith networks connect youth, families and volunteers from different social and religious backgrounds to share experiences and strengthen mutual trust and understanding. Adyan’s academic branch, the Institute of Citizenship and Diversity management, conducts training and research, facilitates conferences, and promotes education on citizenship and coexistence. In 2007, Adyan launched the Alwan Program for Education on Coexistence, which establishes social clubs in religiously diverse schools. The clubs, which build social cohesion and reduce intolerance among children, have reached over 4,158 students in 42 Lebanese schools. Building on their work in education, Adyan partnered with the Ministry of Education in Lebanon to reform curricula and reshape the way that diversity is addressed in schools.

Adyan promotes pluralism by helping divergent groups find common ground. Despite the current climate of religious tension in the region, Adyan is forging an inspiring vision for inclusive communities and spiritual solidarity across Lebanon and the Middle East.

Lebanon is one of the most religiously diverse countries in the Middle East. Religion is deeply intertwined with every aspect of society – from government to education. Political divisions along sectarian lines have contributed to past conflicts, including the Lebanese Civil War (1975-1990). The recent rise of violent extremism and arrival of 1.5 million Syrian refugees have exacerbated tensions. In a country where religion has often divided people, Adyan Foundation’s work to break down cultural and religious barriers and promote openness towards others is crucial to building peace. Adyan has now extended its work beyond Lebanon, with recent projects building toward social cohesion and inclusive citizenship in Iraq.

The “Learning History that is not yet History” Team

“It is very significant to our team to be receiving international recognition for work we have been developing with minimal support for over 16 years. Dealing with the sensitive history of the 1990s Yugoslav wars in our classrooms is very difficult for teachers. We have personal connections to this topic and many, including this team, have buried the topic for decades. It is now the moment to face the past responsibly and to teach about the 1990s conflicts, in order to build a future of mutual understanding, peace and reconciliation.”

Bojana Dujkovic, representative of the award winner, the ‘Learning History that is not yet History’ team

The Team’s Story

A group of students bend over a picture depicting a Bosnian soldier from the 1990s conflicts. Another group studies an image of people walking through the rubble-filled streets of Vukovar, Croatia in 1991. “What do you see?” they are asked. “How does it make you feel? What do you think the photographer is trying to show you?” Discussing a photograph may seem like a straightforward learning exercise, but in the states of the former Yugoslavia, it is much more complex.

In schools, the wars are either ignored or taught in simplistic, one-sided ways, which hinder compassion for people of other ethnic groups. A group of history and education specialists from across the Western Balkan region want to change this. In 2003, they formed a unique regional network which has since expanded to include members from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro, Serbia, Macedonia, Kosovo and Slovenia. The teachers originate from different cultural, ethnic, professional and religious backgrounds. Having all lived through the 90s conflicts in their countries, they have put aside their personal biases to come together to promote the responsible teaching of the past.

Recognizing the danger that simplistic and nationalistic narratives pose to a peaceful society, they set out to provide an alternative approach. They believe that teachers and students must be presented with multiple perspectives on the wars and encouraged to think critically and empathetically about history.

In 2016, the network of historians and educators from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia partnered with the Association of European Educators of History (EUROCLIO) and launched a project that later gave its name to the team, “Learning history that is not yet history” (LHH).

Recognizing that teachers often feel ill-equipped and unsupported to teach these sensitive topics in a way that goes against a dominant, ethnocentric story, LHH created an online database of free resources. These books, articles, videos and photographs support and motivate educators to teach about the 1990s wars using multiple perspectives in ways that do not victimize or blame others. Instead of presenting a specific interpretation of events, LHH focuses on the daily lives of people involved in the conflicts to foster a sense of shared experience.

The partnership and collaboration of LHH represents the first time that history educators from the countries involved in the 1990s wars have reviewed the available educational resources on the topic. The results of their project – a database, teaching materials, and training sessions for teachers – provide the only non-biased approach to learning and teaching about the recent wars.

LHH is giving students and teachers the tools to fight against the kind of division and narrow thinking that could lead to new conflicts. By stimulating discussion, reflection and the recognition of shared experience, LHH is using history as a powerful tool to build sustainable peace in their region.

The conflicts that took place across the Former Yugoslavia during the 1990s continue to have a deep impact on people’s lives. Relations between different states and ethnic groups are sensitive and discussions around the wars remain controversial. The 1990s are remembered across the Western Balkans in uneven and often conflicting ways. Efforts to face the past have been very slow and one-sided. The wars have not been taught in schools until recently. Certain interpretations of history are promoted by political elites as the “official” story. This history is then used to re-shape ethnic and political identities in ways that marginalize and exclude certain groups while amplifying nationalism. These narratives carry over into the education system.

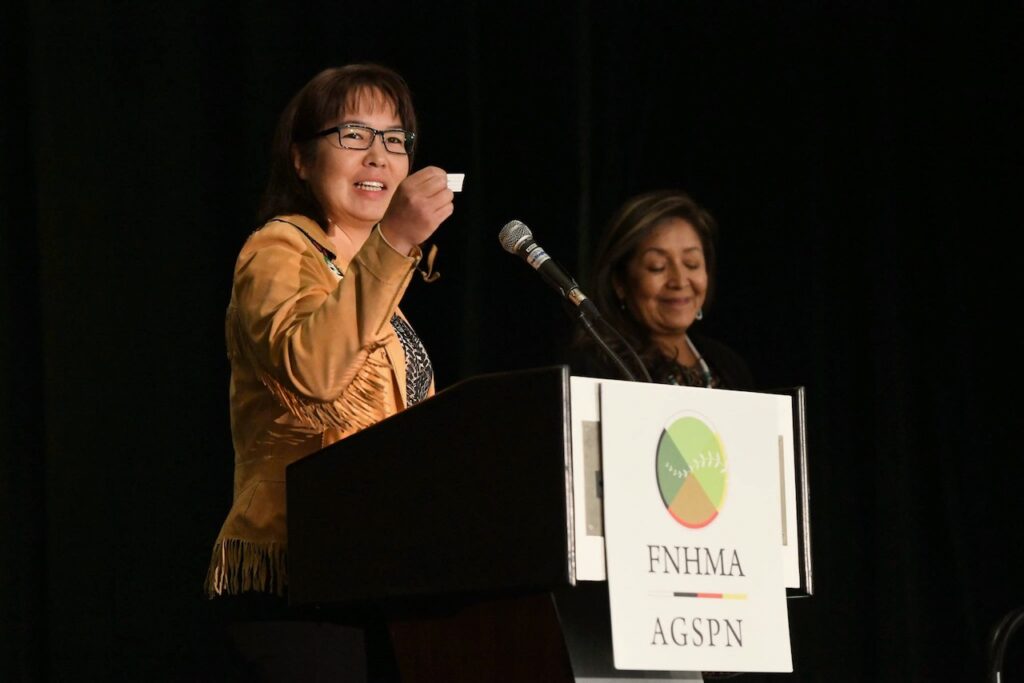

Rose LeMay

Rose’s Story

Rose LeMay is from the Taku River Tlingit First Nation in northern British Columbia, Canada. A survivor of the Sixties Scoop, the mass removal of Indigenous children from their homes and families that took place in Canada throughout the 1960s, Rose was taken from her community as a baby and raised by a non-Indigenous family. She had to figure out who she was, far away from anyone who looked like her. She experienced racism regularly. Rose came to recognize that her experience gave her a unique opportunity. She had a foot in two worlds, and she resolved to use her position to increase understanding between those worlds and to build a more pluralistic Canada so that her children would not have to experience the discrimination that she did.

Rose spent 20 years working for the Government of Canada, advocating for a more inclusive health system for Indigenous communities, with a focus on mental health. She led the development of a mental health plan for survivors and attendees of the Residential School system who were testifying at the first national Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) event, and in 2016, she led the World Indigenous Suicide Prevention Conference abut culture as a protective factor, the first to be hosted in Canada.

In 2017, Rose founded the Indigenous Reconciliation Group (IRG) to provide adult education and organizational training on Indigenous cultural competence and reconciliation. The IRG raises awareness about the types of racism that exist for Indigenous people in Canada and how Canadians can work together for Indigenous inclusion—whether by ensuring that indigenous clients receive the same quality of care from frontline services providers or by supporting organizations to educate their employees about racism.

Through the IRG, Rose raises awareness via media outreach and speaking engagements. She helps organizations shift their policies and programs to support reconciliation by implementing the TRC’s Calls to Action. Rose’s courses have reached more than 5,000 people across Canada. The Government of Nunavut and British Columbia’s Ministry of Indigenous Relations and Reconciliation have sought out her trainings, with the latter engaging with IRG specifically to consult on a strategic plan to enact the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

As Rose points out, reconciliation is a journey that Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples in Canada choose to take together, with leaders and allies and change-makers across all sectors of Canadian society pushing to do better for each other and for the country.

Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) was established in 2008 with the purpose of documenting the history and lasting impacts of the Residential School system, through which 150,000 indigenous children were taken from their communities and sent to state-funded institutions where they were stripped of their culture and severely mistreated. The TRC determined that the Residential School systems amounted to a cultural genocide of Indigenous people. In addition to guiding Canadians through the difficult discovery of the facts behind the Residential School system, the TRC was meant to lay the foundation for lasting reconciliation across Canada. In 2015, the Commission came up with 94 Calls to Action that were presented to the Government of Canada regarding reconciliation between Canadians and Indigenous peoples. In 2021, the unmarked graves of thousands of Indigenous children were uncovered across former Residential School sites. These tragic reminders of the legacy of the Residential School system highlight the gravity of the violence, the importance of this conversation and the urgency of concrete actions toward reconciliation.

Puja Kapai

“By honouring my work in advancing social justice in relation to race, gender and minority rights this Award renders visible the lived realities of all those who are routinely marginalised and experience systemic exclusion and discrimination”

Puja Kapai

Puja’s Story

Growing up as an ethnic minority in the racially homogenous society of Hong Kong, Puja Kapai faced barriers to education from an early age. Racial segregation in schools was common practice, so Puja enrolled in a public school with a high concentration of ethnic minority students. The school would become one of a handful of designated institutions for ethnic minority children. While her ethnic Chinese counterparts attended Cantonese lessons, a language that would enable them to pursue better jobs in the Hong Kong workforce, Puja was ushered into the music room for self-study sessions along with other ethnic minority students.

Despite this unequal footing, Puja has gone on to become a widely published researcher, lawyer, professor and social justice advocate. She combines in-depth empirical research with grassroots mobilization and advocacy to enact lasting change in Hong Kong. Her comprehensive report on the status of ethnic minorities in Hong Kong brought together extensive data to present—for the first time—how the systemic nature of racial discrimination is embedded across multiple domains, including education, employment and housing. Puja’s work demonstrates the importance of looking at interlocking factors, such as gender, race, age and immigration status, which, in turn, underscores the need for an intersectional approach to understanding the root causes of inequalities in Hong Kong.

Most impactful was Puja’s careful illustration of the detrimental effect segregated schools had on the lives of Hong Kong’s ethnic minorities, resulting in the loss of opportunities and deprivation across multiple domains. She presented this research to the Hong Kong government and to three United Nations treaty bodies reviewing Hong Kong’s obligations relating to racial discrimination, children’s rights and human rights more broadly. In 2014, as a direct result of Puja’s research and advocacy, and in collaboration with local non-governmental organizations leading the work on these issues, the Hong Kong government abolished the official policy designating separate schools for racial minority children, and the government introduced a Chinese Language Curriculum Second Language Learning Framework for public schools.

This is but one example of what a tremendous force for change Puja has become in her society. Her work addresses issues of education, domestic violence, children’s rights, gender-based violence, discrimination based on race, gender, religion and sexual orientation, and unconscious bias. Puja’s work has guided lawmakers, government departments and civil society to develop laws and policies using an intersectional approach, across a range of areas, to ensure equal protection for everyone. She has successfully advocated for the revision of governmental procedural guidelines for handling cases of child abuse, child maltreatment, domestic and sexual violence involving ethnic minorities, as well as the improvement of training programs for police officers handling cases involving ethnic minorities. Her research and advocacy have also led to targeted measures by the government to support ethnic minorities.

Having experienced the harmful effects of exclusion and prejudice first-hand, Puja works tirelessly to advance equal rights for all people in Hong Kong. Whether she is researching, advocating, mobilizing or teaching her students how to recognize and address the social justice issues happening around them, Puja is driven by her knowledge that every Hong Konger deserves equal respect and opportunity, and that her city’s laws and policies will be strengthened by their inclusion and recognition of their equal dignity.

While Hong Kong has a global reputation as an international hub, it is a racially homogenous city, with ethnic Chinese people making up about 92 percent of the population. Ethnic minorities account for 8 percent of Hong Kong’s population. Among them, 4.2 percent are foreign domestic workers on temporary work arrangements under a specific labour scheme, and 3.8 percent are longer-term resident ethnic minorities. Ethnic minorities face limited opportunities, bias and systemic discrimination in many areas, including education, employment, housing and health care. Language barriers exacerbate the structural challenges minorities face. Without an education in Cantonese or Mandarin, ethnic minorities are more likely to work in low-paid positions. Poverty and unequal access to essential social services disproportionately affect these communities.

Hand in Hand: Center for Jewish-Arab Education in Israel

“With each new student, school, community, and partner we are sending out ripples of change that lay strong foundations for an equal, pluralistic society for Jews and Arabs, where everyone feels they fully belong.”

Dani Elazar, CEO Hand in Hand: Center for Jewish-Arab Education in Israel

Hand in Hand’s story

In the Max Rayne Hand in Hand Jerusalem School, co-teachers Sirin and Chaim welcome their second-grade students after summer break. Sirin and Chaim ask half the class to hold hands and circle the other half while music plays. When the music stops, the students face each other. Sirin says, in Arabic, “Ask your friend: What excites you about coming back to school?” The next time the music stops, Chaim prompts, in Hebrew, “What was the most fun thing you did over the summer break?” Over the course of the school year, these Arab and Jewish children will study together in both Hebrew and Arabic, learning one another’s language, history and heritage. They will celebrate the stories, songs, symbols and traditions of Muslim, Jewish and Christian holidays. They will learn, as they are learning in this circle activity, to listen to each other, to trust each other and to laugh with each other.

This vibrant, multicultural atmosphere is characteristic of Hand in Hand schools, but it is rare to find outside of Hand in Hand. Israel’s education system is segregated along religious and ethnic lines. Often, individuals from different communities do not encounter each other until they are young adults, at which point many are locked into one or the other side of a complex and violent conflict that has been going on for generations.

In 1998, Hand in Hand introduced a transformational alternative to this segregated reality by bringing together its first integrated, bilingual classes of Jewish and Arab students. Recognized by the Israeli Ministry of Education, Hand in Hand’s award-winning public schools now serve over 2,000 Jewish and Arab students, in preschool through grade 12, in locations across Israel. Teams of Jewish and Arab co-teachers use innovative methods to enrich students’ sense of identity while fostering respect for their peers. Equality, empathy, responsibility and respect are the pillars of a Hand in Hand education. Students learn to think critically, disagree respectfully and consider history from multiple perspectives.

Over the years, Hand in Hand’s model has broadened from a network of schools into a three-part model of shared living and learning that includes integrated schools, inclusive communities and more and more public partnerships. Hand in Hand staff, parents, students and alumni are part of a countrywide movement driven by shared values and the choice to build sustainable change that extends far beyond school walls. Hand in Hand’s community programs engage thousands in building a proud shared society of inclusion, equality and respect through dialogue and language programs, cultural events and celebrations, lectures and workshops, civic engagement and activism, leadership seminars and countrywide conferences. By collaborating with municipalities and the Ministry of Education, Hand in Hand’s work is increasingly influencing the national education system from within. Every day, in Hand in Hand schools and communities across the country, thousands of children and adults learn not just to tolerate one another but to respect, embrace and learn from each other. They discover that diversity is not a threat. Rather, it is an enriching experience and a tremendous opportunity to grow, as individuals and as a society.

Mistrust and fear between Arab and Jewish communities within Israel is deep, stemming not only from the Israeli-Palestinian conflict but also from the spatial separation of Jewish and Arab communities, as well as the division of the public education system into siloed school streams along ethnic and religious lines. This greatly contributes to the divide between the two groups. Most Jewish students in Israel have little to no exposure to Arabic or Arab culture in a school setting, with both communities denied the opportunity to build the inter-communal relationships and partnerships that are fundamental to building a more pluralistic society.